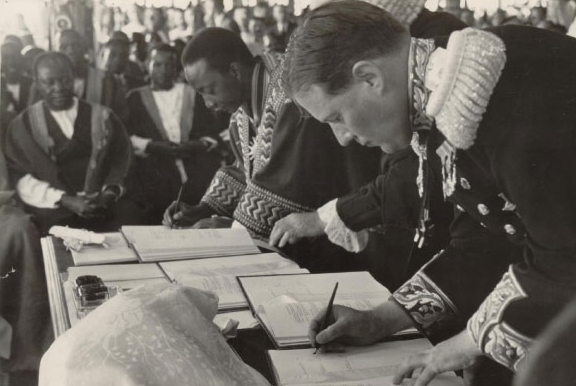

Bell, Luzira, in 1956.

By Barbara Kimenya

Posted Saturday, September 26 2015

IN SUMMARY

Adventures. Young and beautiful British-born Barbara arrived at Port Bell by ferry from Bukoba, Tanzania to start a whole new life after her marriage had fallen apart. It is a life that would see her mix with ordinary Baganda and bring her close to their king. In the first part of our serialisation of her unpublished book,Tales from Mutesa’s Palace, she writes about her first days in the country.

SHARE THIS STORY

In 1956, we docked at Port Bell in Luzira on a bright morning after a whole night journey across Lake Victoria from Bukoba in Tanzania on a steamer; the trim little vessel that plied Lake Victoria calling at Bukoba, Mwanza and Kisumu as well as Port Bell once a week.

The overnight voyage from Bukoba could have been pleasant, but it wasn’t. While the officers and crew were as trim as ever in their crisp whites, and a fantastic six course dinner was served, the few comfortable cabins had been booked weeks earlier, and the deck was packed solid with workers on their way to the Ugandan sugar plantations.

I was lucky to sleep on a chair, Topha my baby son on my knee, and my elderly Scottie, Shadrach, at my feet. Other travellers sprawled wherever they found space: mostly on the floor.

At first there was an element of fun in the way we were ‘camping’, but the joking ground to a sudden halt after a nun laid herself out on the centre table to sleep, closed her eyes and placed her hands in an attitude of prayer, for all the world like an effigy on a mediaeval tomb. The air of sanctity did for us all.

Eddie and Nancy, a Scottish couple, waited for me on the dock. We had been acquaintances rather than close friends in Bukoba, and it remains a source of wonder to me that they should have done so much to extricate me from the messy marriage breakup. Thanks to them, I was to arrive in Kampala with lodgings and a secretarial job already lined up.

Beautiful city

Kampala was then at the height of its reputation as East Africa’s most beautiful city, as well as the most sophisticated. As on previous visits, I couldn’t get enough of the smart shops displaying goods we only dreamed about on the other side of the lake. It was all a far cry from Bukoba, where the main street was either a stretch of mud or dust, depending on the weather, flanked by rickety wooden buildings housing various general stores.

There was also a victorious atmosphere in Kampala, at least among the Baganda, at the time I landed at Port Bell. Only a few months earlier, October 17, 1955 to be exact, the Kabaka of Buganda, His Highness Mutesa II, had returned from exile in Britain, into which he had been unceremoniously bundled by Governor Andrew Cohen on November 30, 1953 for refusing to accept the British government’s dictates on several important issues.

Eddie and Nancy had arranged for me to board with a retired nurse called Betty, whose rambling old house faced Makerere University. Her only other boarder was an old West Indian lawyer, and the two of them were frequently tight as ticks on pink gins. Betty, from the start, made me, my son and my dog very welcome, and fed us well.

In fact I was so grateful for having come to roost in such homely surroundings, and being sure of a job to go to next day, that on my first Sunday in Kampala, I attended mass at the university Roman Catholic chapel.

Ms Barbara Kimenye. Courtesy photo.

It was an uplifting experience, fully in keeping with my current state of pious thanksgiving. The priest preaching the sermon was particularly inspiring. That Sunday was the only time I was privileged to see and hear him, because a few days later he ran off with a lecturer’s wife.

My new job was in a shop on Salisbury Road (now Nkrumah Road) which dealt in paint and iron bars. Betty had found a young sensible Munyoro, Joyce, to look after Topha, so I didn’t have to worry about rushing home at lunchtime. The work could hardly be termed back-breaking, and most of the day was spent in chatting to the customers who were mainly building contractors.

Worklife

Apart from me sitting behind a little-used typewriter, there was a salesman-cum-storekeeper, a porter-cum-messenger, and the boss, a courteous, reserved man who was not very much in evidence, and who ran off with the takings three weeks after I joined his staff. I gradually understood that running off was practically a disease in Uganda.

His replacement was sent from Kenya by our head office. It was one of my first close encounters with a Kenyan white, and suddenly the whole Mau Mau business started to make sense. Within two minutes of Sandy’s arrival in our office/shop, I could have cheerfully killed him.

Short, tubby and as sandy as his name implied, he made a bee-line for the Kampala Club, then strictly Europeans only, in the hope of finding someone who could wangle an invitation to State House for him. He spoke to the salesman-cum-storekeeper and porter-cum-messenger as though they belonged to a species lacking human intelligence, when he was not loudly asserting that all Africans were thieves.

He was so anxious to be rid of me – since I too clashed with his colour scheme – that he went to the trouble of getting me another job with an insurance company which paid almost twice as much. The excuse was “am bringing out a European secretary as my personal aide”!

While I still worked for him, however, we three subordinate staff hated him: not solely for how he viewed us, but because he never missed an opportunity of running down our previous boss to whoever happened to be in the shop. Our sympathies were with the chap who had run away with the takings. We considered that if he had to deal with a head office staffed with the Sandys, he was perfectly entitled to grab what he could and run.

Then I was suddenly, unbelievably pregnant! While trying to explain to Mr Burbridge, the principal immigration officer, why I believed I did not, because of family connections, need a work permit in Uganda, the room swam, there was a weird buzzing in my ears, and the next thing I knew was his secretary pressing a glass of water to my lips. On Mr Burbridge’s advice, I consulted a doctor - and couldn’t believe my ears when the man pronounced me three months pregnant.

It was the most astounding moment of my life. I mean, what are you supposed to do when you’ve made a grand exit, and two months later find yourself carrying the object of your scorn’s baby? I did what I was very good at doing in those days. I tried to put the awkward business out of my mind, in the hope that it would go away.

Meanwhile, staying in town for lunch, and usually eating at a pleasant, cheap restaurant on the Wandegeya side of Kampala Road, I met dozens of Ugandans whom I had known as students frequenting East Africa House behind the Cumberland Hotel at Marble Arch in London. I also made many new friends, regulars at the same place, including the infamous Ted Jones and his Muganda wife, Mary. These two became very special over the years. I missed them when they eventually emigrated to Australia.

Meeting friends

And all these people turned out to be real friends. Most of the old ones from the East Africa House days introduced me to their families and were there with help whenever they thought I needed it. Foremost in this respect was Joe Zake, newly-established as a practising lawyer in offices in a rickety wooden building.

He took me in hand, made me face up to the fact that another baby was on the way, whether or not I liked it, and found a house at a rent I could afford, £5 a month, to be precise, below the Roman Catholic cathedral on Rubaga Hill. He then supplied such essentials as a paraffin stove, some sufurias, and a bread knife which survived long enough to go with my youngest son when 20 odd years later he went to Aston University.

Apart from the need to-learn to stand on my own feet, if I was determined to make the separation from my husband permanent, a further reason for leaving Betty was that her house bordered a swamp, and Topha went down with a hideous attack of malaria.

It was a shock, after running down to Mulago hospital in the middle of the night with a screaming child, to be told by the Ugandan doctor that I ought to have taken the baby to the European Hospital (former Ugandan Television studios in Nakasero). Only when I argued that my son was fathered by a full-bloodied African, and that he had been delivered by an African doctor (Dr Matwale, later director of medical services, Tanzanian govt) was Topha given treatment.

Earlier, it had never entered my head that a colour bar operated in a place as liberal as Uganda. There was a great deal of mixing going on all over the place, practically everywhere. But whereas my Ugandan friends accepted me without question, officialdom seemed to have a problem reconciling my half-tone colour with my British accent. In other words, officialdom, or the people wielding it, did not know where or to whom I belonged.

Moving to Rubaga hill

Shadrack, my Scottish Terrier, died shortly before we left Betty’s place. He caught tick fever, and, being an imported dog, was past saving before it was diagnosed. He was nine years old, and losing him was the saddest of happenings. There was slight consolation in knowing that the year and a half he spent in Africa, after my mother flew him out to me in what was then Tanganyika, were probably the best of his life. It had been a time of wanderings in huge gardens, investigating strange smells and creatures, and never being shut up for hours on end in a stuffy London flat. Still, I missed him as I had never before missed anybody.

The house we rented from a true gentleman called Peter Sendikwanawa, a rich landowner who lived in Masaka, lay across the valley from Lubiri, the Kabaka’s palace, and must have been one of the earliest Western-type buildings in Buganda. It stood in about an acre of neglected garden, and was approached by a gravel drive flanked by gnarled frangipani trees.

A wide verandah enclosed six large rooms which led directly into one another: in the old days, the Baganda didn’t believe in wasting space on passages, although they never seemed to count the cost of extra doors. It seemed enormous to Joyce and me; and the fact that there was no electricity or running water, and that the outside lavatory was in a state of collapse was the least of our worries.

We soon got used to going together to relieve ourselves, so that if either of us disappeared down the pit latrine, the other could run for help. We moved into the house with a bed each, a cot for Topha, and a few packing cases draped in curtaining for seats. There was no need to curtain the windows since they had shutters. And in next to no time our household expanded to include a short, black, wire-haired dog, one of whose parents must surely have been a Scottie, who the neighbours called ‘Puppy’, but who we promptly named ‘Mzee’.

Mzee really did not belong to anybody, and everybody fed him, but he slept on our verandah and we felt that gave us rights of ownership.

Then Alex, a Munyarwanda water-carrier, who used to bring us three or four 4-gallon cans of water twice a day, on a heavy wooden barrow, and charged us five cents a can, quietly moved into a tumbledown mud and wattle outhouse which Joyce said was supposed to be our kitchen.

Extra hands

He slid onto our payroll with equal discretion. First he started tidying up the garden, and gradually the most delicate and attractive floral arrangements in jam jars decorated every room. Next he took on the washing of the floors, and produced a rich gleam which we never suspected they possessed.

But Alex really made his mark when he changed his ragged shorts and vest for a snowy white kanzu and red fez, and took to welcoming visitors at the door with great dignity. The contrast between his style of welcome, and their having to sit on packing cases, was like Claridges’ doorman ushering guests into a roadside cafe.

I was able to pay him a salary because around the same time that Alex attached himself to us, I went to work for the insurance company where the work was interesting, my colleagues friendly, and of course the pay worthwhile.

Looking back on this period of my life, I still see it as the happiest ever. Money was tight, but we ate. I walked an average of four miles a day, there and back to work. Yet I don’t recall ever feeling frightened or miserable, or even exceptionally tired.

I was exhilarated every time I entered that frangipani lined driveway, and saw Joyce on the verandah with a spruced up Topha and the teapot at the ready. It was a great day when I came back from the city with ‘Toro’ chairs for the three of us,(Toro chairs were made of a vegetable fiber and tree branches, and cost about five shillings each). I have since been in a position to buy more conventionally smart furniture, but none of it has generated so much pleasure.

Dog tales

It was her idea that we should bath Mzee, for, as she pointed out, the old dog carried ticks the size of grapes and, judging from the way he scratched, was a walking home for hundreds of fleas. Somehow we managed to throw him into a bowl of disinfectant, but he went wild – snapping and howling, and drenching us in his attempt to escape. Afterwards, he disappeared for a week, then he came back as lousy as ever. We never tried bathing him again.

Our Baganda neighbours were amused by this performance. Most of their little mud and wattle houses were screened by matooke plantations, so we didn’t see much of each other, but we often met on Rubaga Road leading to the cathedral, or on the main track running along our side of the hill. They had, of course, heard Mzee’s terrorised yells, and some had seen him, soaking wet and wild-eyed, tearing through the bushes.

They thanked Joyce and me for trying to clean the old dog – really because the Baganda customarily have a very gracious way of giving thanks for everything and anything, but couldn’t resist making a few sly jokes at our expense. One old man said bluntly that we were lucky not to have been bitten, and told us to leave well alone if we didn’t want to catch rabies.

Accommodative neighbours

The nicest thing about our neighbours was their quiet acceptance of other people’s oddities as commonplace, which may be why, as I soon discovered, Rubaga had more than its fair share of unusual characters.

Mr Macken, for instance, an Irish Catholic lawyer, who lived a spartan life on the other side of the hill, took his dogs for a walk at exactly the same time every evening, and seemed to spend more time in church than the White Fathers who manned the cathedral. He was very taciturn where women were concerned. A greeting from any of us was acknowledged with a grunt and the avoidance of eyes.

My next door neighbour, Miriam Daly, also Irish, contended that he [Macken] thought we all wanted to tamper with his virtue.... It was well known that Mr Macken had been doing the First Fridays for years: i.e. taking Holy Communion on the first Friday of each of nine months to ensure receiving the Last Sacraments on his deathbed. We were all naturally perplexed when the poor man dropped dead at the roadside, on his way to fulfil yet another set of First Fridays.