Elkins had come to prominence in 2005 with a book that exhumed one of the nastiest chapters of British imperial history: the suppression of Kenya’s Mau Mau rebellion. Her study, Britain’s Gulag, chronicled how the British had battled this anticolonial uprising by confining some 1.5 million Kenyans to a network of detention camps and heavily patrolled villages. It was a tale of systematic violence and high-level cover-ups.

It was also an unconventional first book for a junior scholar. Elkins framed the story as a personal journey of discovery. Her prose seethed with outrage. Britain’s Gulag, titled Imperial Reckoning in the US, earned Elkins a great deal of attention and a Pulitzer prize. But the book polarised scholars. Some praised Elkins for breaking the “code of silence” that had squelched discussion of British imperial violence. Others branded her a self-aggrandising crusader whose overstated findings had relied on sloppy methods and dubious oral testimonies.

By 2008, Elkins’s job was on the line. Her case for tenure, once on the fast track, had been delayed in response to criticism of her work. To secure a permanent position, she needed to make progress on her second book. This would be an ambitious study of violence at the end of the British empire, one that would take her far beyond the controversy that had engulfed her Mau Mau work.

That’s when the phone rang, pulling her back in. A London law firm was preparing to file a reparations claim on behalf of elderly Kenyans who had been tortured in detention camps during the Mau Mau revolt. Elkins’s research had made the suit possible. Now the lawyer running the case wanted her to sign on as an expert witness. Elkins was in the top-floor study of her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when the call came. She looked at the file boxes around her. “I was supposed to be working on this next book,” she says. “Keep my head down and be an academic. Don’t go out and be on the front page of the paper.”

She said yes. She wanted to rectify injustice. And she stood behind her work. “I was kind of like a dog with a bone,” she says. “I knew I was right.”

What she didn’t know was that the lawsuit would expose a secret: a vast colonial archive that had been hidden for half a century. The files within would be a reminder to historians of just how far a government would go to sanitise its past. And the story Elkins would tell about those papers would once again plunge her into controversy.

Nothing about Caroline Elkins suggests her as an obvious candidate for the role of Mau Mau avenger. Now 47, she grew up a lower-middle-class kid in New Jersey. Her mother was a schoolteacher; her father, a computer-supplies salesman. In high school, she worked at a pizza shop that was run by what she calls “low-level mob”. You still hear this background when she speaks. Foul-mouthed, fast-talking and hyperbolic, Elkins can sound more Central Jersey than Harvard Yard. She classifies fellow scholars as friends or enemies.

The Mau Mau uprising had long fascinated scholars. It was an armed rebellion launched by the Kikuyu, who had lost land during colonisation. Its adherents mounted gruesome attacks on white settlers and fellow Kikuyu who collaborated with the British administration. Colonial authorities portrayed Mau Mau as a descent into savagery, turning its fighters into “the face of international terrorism in the 1950s”, as one scholar puts it.

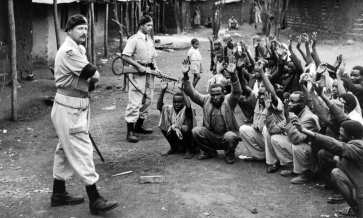

The British, declaring a state of emergency in October 1952, proceeded to attack the movement along two tracks. They waged a forest war against 20,000 Mau Mau fighters, and, with African allies, also targeted a bigger civilian enemy: roughly 1.5 million Kikuyu thought to have proclaimed their allegiance to the Mau Mau campaign for land and freedom. That fight took place in a system of detention camps.

Elkins enrolled in Harvard’s history PhD programme knowing she wanted to study those camps. An initial sifting of the official records conveyed a sense that these had been sites of rehabilitation, not punishment, with civics and home-craft classes meant to instruct the detainees to be good citizens. Incidents of violence against prisoners were described as isolated events. When Elkins presented her dissertation proposal in 1997, its premise was “the success of Britain’s civilising mission in the detention camps of Kenya”.

But that thesis crumbled as Elkins dug into her research. She met a former colonial official, Terence Gavaghan, who had been in charge of rehabilitation at a group of detention camps on Kenya’s Mwea Plain. Even in his 70s, he was a formidable figure: well over six feet tall, with an Adonis-like physique and piercing blue eyes. Elkins, questioning him in London, found him creepy and defensive. He denied violence she hadn’t asked about.

“What’s a nice young lady like you working on a topic like this for?” he asked Elkins, as she recalled the conversation years later. “I’m from New Jersey,” she answered. “We’re a different breed. We’re a little tougher. So I can handle this – don’t worry.”

In the British and Kenyan archives, meanwhile, Elkins encountered another oddity. Many documents relating to the detention camps were either absent or still classified as confidential 50 years after the war. She discovered that the British had torched documents before their 1963 withdrawal from Kenya. The scale of the cleansing had been enormous. For example, three departments had maintained files for each of the reported 80,000 detainees. At a minimum, there should have been 240,000 files in the archives. She found a few hundred.

But some important records escaped the purges. One day in the spring of 1998, after months of often frustrating searches, she discovered a baby-blue folder that would become central to both her book and the Mau Mau lawsuit. Stamped “secret”, it revealed a system for breaking recalcitrant detainees by isolating them, torturing them and forcing them to work. This was called the “dilution technique”. Britain’s Colonial Office had endorsed it. And, as Elkins would eventually learn, Gavaghan had developed the technique and put it into practice.

Later that year, Elkins travelled to the rural highlands of Central Kenya to begin interviewing former detainees. Some thought she was British and refused to speak with her at first. But she eventually gained their trust. Over some 300 interviews, she heard testimony after testimony of torture. She met people such as Salome Maina, who had been accused of supplying arms to the Mau Mau. Maina told Elkins she had been beaten unconscious by Kikuyu collaborating with the British. When she failed to provide information, she said, they raped her using a bottle filled with pepper and water.

Elkins had uncovered 'a murderous campaign that left tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, dead'

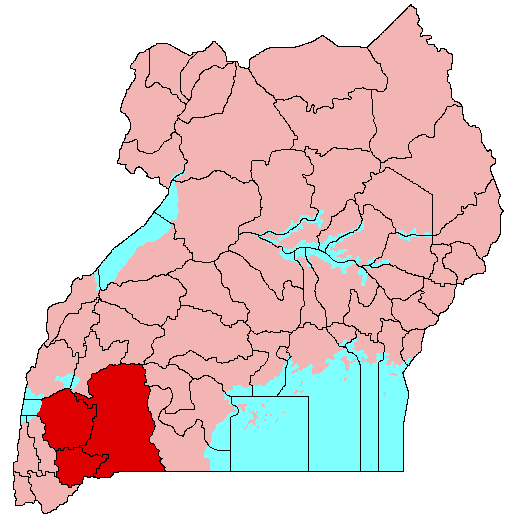

Elkins’s fieldwork brought to the surface stories repressed by Kenya’s policy of official amnesia. After the country gained independence in 1963, its first prime minister and president, Jomo Kenyatta, a Kikuyu, declared repeatedly that Kenyans must “forgive and forget the past”. This helped contain the hatred between Kikuyu who joined the Mau Mau revolt and those who fought alongside the British. In prying open that story, Elkins would meet younger Kikuyu who didn’t know their parents or grandparents had been detained; Kikuyu who didn’t know the reason they had been forbidden to play with their neighbour’s children was that the neighbour had been a collaborator who raped their mother. Mau Mau was still a banned movement in Kenya, and would remain so until 2002. When Elkins interviewed Kikuyu in their remote homes, they whispered.

Elkins emerged with a book that turned her initial thesis on its head. The British had sought to quell the Mau Mau uprising by instituting a policy of mass detention. This system – “Britain’s gulag”, as Elkins called it – had affected far more people than previously understood. She calculated that the camps had held not 80,000 detainees, as official figures stated, but between 160,000 and 320,000. She also came to understand that colonial authorities had herded Kikuyu women and children into some 800 enclosed villages dispersed across the countryside. These heavily patrolled villages – cordoned off by barbed wire, spiked trenches and watchtowers – amounted to another form of detention. In camps, villages and other outposts, the Kikuyu suffered forced labour, disease, starvation, torture, rape and murder.

“I’ve come to believe that during the Mau Mau war British forces wielded their authority with a savagery that betrayed a perverse colonial logic,” Elkins wrote in Britain’s Gulag. “Only by detaining nearly the entire Kikuyu population of 1.5 million people and physically and psychologically atomising its men, women, and children could colonial authority be restored and the civilising mission reinstated.” After nearly a decade of oral and archival research, she had uncovered “a murderous campaign to eliminate Kikuyu people, a campaign that left tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, dead”.

Elkins knew her findings would be explosive. But the ferocity of the response went beyond what she could have imagined. Felicitous timing helped. Britain’s Gulag hit bookstores after the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had touched off debate about imperialism. It was a moment when another historian, Niall Ferguson, had won acclaim for his sympathetic writing on British colonialism. Hawkish intellectuals pressed America to embrace an imperial role. Then came Bagram. Abu Ghraib. Guantánamo. These controversies primed readers for stories about the underside of empire.

Enter Elkins. Young, articulate and photogenic, she was fired up with outrage over her findings. Her book cut against an abiding belief that the British had managed and retreated from their empire with more dignity and humanity than other former colonial powers, such as the French or the Belgians. And she didn’t hesitate to speak about that research in the grandest possible terms: as a “tectonic shift in Kenyan history”.

Some academics shared her enthusiasm. By conveying the perspective of the Mau Mau themselves, Britain’s Gulag marked a “historical breakthrough”, says Wm Roger Louis, a historian of the British empire at the University of Texas at Austin. Richard Drayton of King’s College London, another imperial historian, judged it an “extraordinary” book whose implications went beyond Kenya. It set the stage for a rethinking of British imperial violence, he says, demanding that scholars reckon with colonial brutality in territories such as Cyprus, Malaya, and Aden (now part of Yemen).

But many other scholars slammed the book. No review was more devastating than the one that Bethwell A Ogot, a senior Kenyan historian, published in the Journal of African History. Ogot dismissed Elkins as an uncritical imbiber of Mau Mau propaganda. In compiling “a kind of case for the prosecution”, he argued, she had glossed over the litany of Mau Mau atrocities: “decapitation and general mutilation of civilians, torture before murder, bodies bound up in sacks and dropped in wells, burning the victims alive, gouging out of eyes, splitting open the stomachs of pregnant women”. Ogot also suggested that Elkins might have made up quotes and fallen for the bogus stories of financially motivated interviewees. Pascal James Imperato picked up the same theme in African Studies Review. Elkins’s work, he wrote, depended heavily on the “largely uncorroborated 50-year-old memories of a few elderly men and women interested in financial reparations”.

Elkins was also accused of sensationalism, a charge that figured prominently in a fierce debate over her mortality figures. Britain’s Gulag opens by describing a “murderous campaign to eliminate Kikuyu people” and ends with the suggestion that “between 130,000 and 300,000 Kikuyu are unaccounted for”, an estimate derived from Elkins’s analysis of census figures. “In this very long book, she really doesn’t bring out any more evidence than that for talking about the possibility of hundreds of thousands killed, and talking in terms almost of genocide as a policy,” says Philip Murphy, a University of London historian who directs the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and co-edits the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. This marred what was otherwise an “incredibly valuable” study, he says. “If you make a really radical claim about history, you really need to back it up solidly.”

Critics didn’t just find the substance overstated. They also rolled their eyes at the narrative Elkins told about her work. Particularly irksome, to some Africanists, was her claim to have discovered an unknown story. This was a motif of articles on Elkins in the popular press. But it hinged on the public ignorance of African history and the scholarly marginalisation of Africanist research, wrote Bruce J Berman, a historian of African political economy at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. During the Mau Mau war, journalists, missionaries and colonial whistleblowers had exposed abuses. The broad strokes of British misbehaviour were known by the late 60s, Berman argued. Memoirs and studies had added to the picture. Britain’s Gulag had broken important new ground, providing the most comprehensive chronicle yet of the detention camps and prison villages. But among Kenyanists, Berman wrote, the reaction had generally been no more than: “It was as bad as or worse than I had imagined from more fragmentary accounts.”

He called Elkins “astonishingly disingenuous” for saying her project began as an attempt to show the success of Britain’s liberal reforms. “If, at that late date,” he wrote, “she still believed in the official British line about its so-called civilising mission in the empire, then she was perhaps the only scholar or graduate student in the English-speaking world who did.”

To Elkins, the vituperation felt over the top. And she believes there was more going on than the usual academic disagreement. Kenyan history, she says, was “an old boys’ club”. Women worked on uncontroversial topics such as maternal health, not blood and violence during Mau Mau. Now here came this interloper from the US, blowing open the Mau Mau story, winning a Pulitzer, landing media coverage. It raised questions about why they hadn’t told the tale themselves. “Who is controlling the production of the history of Kenya? That was white men from Oxbridge, not a young American girl from Harvard,” she says.

On 6 April 2011, the debate over Caroline Elkins’s work shifted to the Royal Courts of Justice in London. A scrum of reporters turned out to document the real-life Britain’s Gulag: four elderly plaintiffs from rural Kenya, some clutching canes, who had come to the heart of the former British empire to seek justice. Elkins paraded with them outside the court. Her career was now secure: Harvard had awarded her tenure in 2009, based on Britain’s Gulag and the research she had done for a second book. But she remained nervous about the case. “Good God,” she thought. “This is the moment where literally my footnotes are on trial.”

In preparation, Elkins had distilled her book into a 78-page witness statement. The claimants marching beside her were just like the people she had interviewed in Kenya. One, Paulo Nzili, said he had been castrated with pliers at a detention camp. Another, Jane Muthoni Mara, reported being sexually assaulted with a heated glass bottle. Their case made the same claim as Britain’s Gulag: this was part of systematic violence against detainees, sanctioned by British authorities. But there was one difference now. Many more documents were coming out.

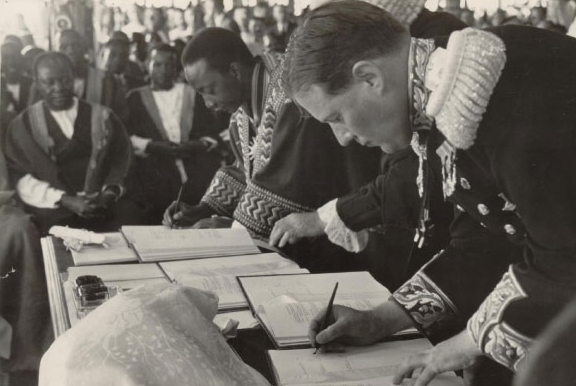

Just as the hearings were set to begin, a story broke in the British press that would affect the case, the debate about Britain’s Gulag, and the broader community of imperial historians. A cache of papers had come to light that documented Britain’s torture and mistreatment of detainees during the Mau Mau rebellion. The Times splashed the news across its front page: “50 years later: Britain’s Kenya cover-up revealed.”