![While there are some WWI cemeteries for European soldiers, there are no burial grounds for Africans [Kathleen Bomani/Al Jazeera] While there are some WWI cemeteries for European soldiers, there are no burial grounds for Africans [Kathleen Bomani/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2018/11/5/ee5ebd9dd727411e831fcb704a7cf262_18.jpg)

Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania - One hundred years ago, on November 11, 1918, the armistice brought an end to the first world war in Europe.

For the countries of East Africa, however, the war would go on for another two full weeks.

From 1914, British Empire soldiers fought a four-year guerrilla campaign against a small German force in East Africa.

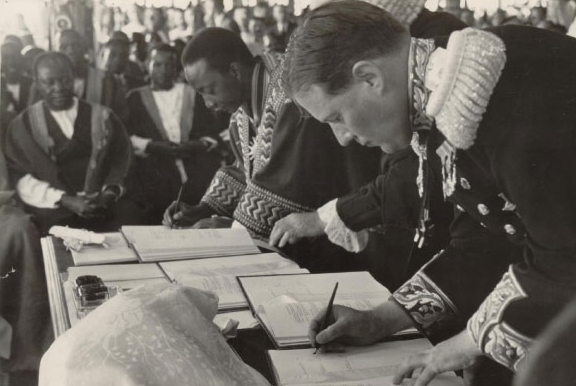

On November 25, 1918, Allied and German forces received and accepted the terms, bringing an end to four years of conflict that had cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of African soldiers and civilians over 750,000 square miles - an area three times the size of the German Reich.

Artist Kathleen Bomani grew up in Tanzania and had been the classroom expert on the first world war.

"I knew it in and out," she says, "or so I thought".

Now, she has just finished her lecture 'What Happened Here' in Berlin as part of the World War I centenary.

Remembrance of WWI remains largely European, even within Tanzania.KATHLEEN BOMANI, ARTIST

It was in her twenties that Bomani realised that not only had the war raged in Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi (then German East Africa) and spread to Mozambique and Zambia, but that it had lasted the entire duration of the war in Europe, and brought comparable devastation.

She had questions. Why was the war considered a sideshow to the trench warfare in Europe? And what traces were left of the fighting? So she travelled through Tanzania, following the routes of African soldiers and carriers, to explore their histories.

Al Jazeera: What happened in East Africa during the First World War? Was it different from the fighting in Europe?

Kathleen Bomani: To understand the scale of the conflicted area, you have to imagine German East Africa as a colony made up much of today's Burundi, Rwanda and the majority of Tanzania.

The size and nature of the land meant that the fighting took on a completely different style.

There was less trench warfare. Instead, the Germans and the Allies chased each other up and down the region, often at a pace of 30km a day.

They levelled villages for supplies and enlisted civilians as soldiers to fight and carriers to shift their supplies. Most soldiers and porters died from malnutrition, fatigue, malaria, tsetse fly and black fever, rather than bullets.

Significantly, the war occurred just seven years after one of the largest acts of resistance against colonial rule, the Maji Maji War.

As a result, the German forces utilised guerrilla tactics that had been successful to them.

Al Jazeera: What was the cost?

Bomani: For German commander Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, the East Africa campaign was as a distraction, with the aim of drawing Allied troops away from the fronts in Europe.

Britain leaned on forces from across its colonies: troops from Ghana, Nigeria, the West Indies, Jamaica, Uganda, Kenya, South Africa.

Together with Allied forces of Belgium and Portugal, their numbers made up 150,000 soldiers. German forces numbered around 25,000.

An old German Hospital built in 1895 is now completely empty in Tang, Tanzania

More staggering was the number of carriers needed over the four years, at a total of more than one million.

And wherever soldiers went, they recruited more. The official loss of life was around 105,000 although these numbers are almost certainly downplayed.

Fundamentally, the deaths of carriers were seen as dispensable and not accurately recorded. We may never know how many Africans died during WWI.

Al Jazeera: You have travelled around Tanzania exploring the traces of the war left on the region. What do they look like?

Bomani: There are no official cemeteries for African soldiers and carriers and there are few traces of the battlefields.

What have endured are large German colonial buildings that became quickly abandoned after 1918: a hospital in Tanga, disused train stations in Moshi, a fort in Lindi and impressive houses for German governors.

A former Missionary Church in the historical Swahile town of Mikindani, Tanzania

The first thing you notice about these buildings is that they are statuesque. They were built to last.

The Germans had clearly intended to keep its colony for a long time, like the British after them.

The second is that they are all empty. These are prime locations, often beachfront or strategic, very public spaces. Despite that, they have not been used. They carry a feeling of unreconciled trauma.

Al Jazeera: You explain in your exhibition that the traces of the war are different in the south of Tanzania…

Bomani: In the south, it is hard to find any trace of the battles. Even at the place of one of the bloodiest battles, Mahiwa, where the death count reached the thousands in just three days, there is little trace of WWI.

There is, however, a church, which would have been a Christian mission from the same era. Such churches kept records of daily life in the run-up to the war: they recorded villagers selling all their livestock so they would have enough money to flee, they recorded student numbers in school plummeting.

Carriers were fully aware that this conflict was fundamentally a colonial project.

Meanwhile, British missionaries wrote opportunistically about the lands and congregations of German missions that would become available to them after the war. Across the southern highlands, these records give a sense of the scale of the war, and that the people in its path universally acknowledged its force.

Al Jazeera: How do you feel, finding these traces of WWI?

Bomani: On the one hand, it is good these traces exist, or you would have a hard time convincing yourself that the war happened here.

On the other, these traces left as they are have not been discussed or unpacked, and so remembrance of WWI remains largely European, even within Tanzania. They are not monuments, but monoliths that signal the colonial past.

Al Jazeera: You say in your exhibition that researching WWI has become a personal undertaking. What do you mean by that?

Bomani: I am Sukuma, a people from northern Tanzania. Traditionally, Sukuma are farmers and they use music to pace themselves through agricultural work.

Through the years of the centenary, I looked into some of the songs focused on those that came from WWI, when Sukuma were heavily recruited as carriers and soldiers by German forces.

While Europe marks 100 years of remembering, we Africans are now just opening that chapter. While the centenary is almost over, it is not too late.

One song that struck me has the lyrics:

'Boulders fighting one another on the plain/ the Germans and the English/ they run about taken to flight/ because of cattle'.

The 'cattle' line means assets: resources, land, livestock, money. In other words, the carriers were fully aware that this conflict was fundamentally a colonial project.

I was struck too by the subversive power of the songs - they contradict the image of the loyal askari soldier, which was used as propaganda throughout wartime. They are a record of the larger African experience during WWI, and it is important to preserve them even as agricultural methods change.

Al Jazeera: How is the WWI history usually remembered in Tanzania? Why do you feel this is important to the future of the country?

Bomani: There are usually memorial services, often in war cemeteries on November 11, instead of the 25. I have visited these cemeteries in Dar es Salaam, Tanga, Moshi, Iringa and there is no acknowledgement of the African soldiers and carriers.

The lack of acknowledgement underscores how vital the Black Lives Matter movement is today. Because even in celebrating one of the most well-known events in history, there still has been a level of omission loss to African lives.

Al Jazeera: Has it been any different for the centenary?

Bomani: This year the University of Dar es Salaam is hosting a conference on German colonial history and experts will be putting themselves to the task of discussing some of the uncomfortable truths of the war in Africa.

There is new talk of including the East Africa campaign in the school curriculum. Ultimately, the nation is beginning to address it and move forward. While Europe marks 100 years of remembering, we Africans are now just opening that chapter. While the centenary is almost over, it is not too late.