African Traditional Revenue and Taxation:

Money in dollar bills seized from a home of the Commissioner General of the Tanzania Revenue Authority is pictured down: Over 20 bags of it:

OBULANGO

Oluguudo Lwa Kabaka Njagala, Mubweenyi

bw'enju ya Kisingiri ewa Musolooza.

Telephone::

Ssentebe - 256 712845736 Kla

Muwanika -256

712 810415 Kla

UGANDA.

Email Links:

info.bazzukulu

babuganda

@gmail.

com.

OMUZIRO:

NKEREBWE

AKABBIRO

Kikirikisi-Mmese etera okuzimba mu kitooke.

OMUTAKA

KIDIMBO.

OBUTAKA

BUDIMBO.

ESSAZA

SSINGO

OMUBALA:

Nkerebwe nkulu esima nga eggalira

Olukiiko lwa Buganda lwanjudde embalirira ya buwumbi 7

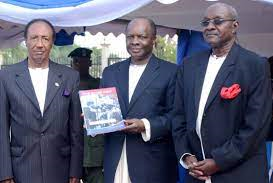

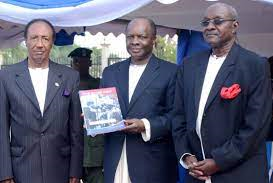

The Kabaka of Buganda launches a book on Ssekabaka Muteesa II struggles:

Posted Friday, 27 May, 2016

By the Monitor, Uganda

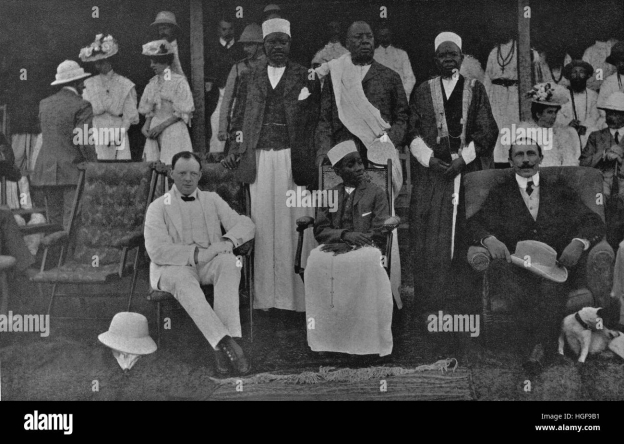

Kabaka Mutebi (centre) with Mr Patrick Makumbi (right) and Dr Colin Sentongo (left) at the book launch at Bulange in Mengo, Kampala.

Kabaka Mutebi (centre) with Mr Patrick Makumbi (right) and Dr Colin Sentongo (left) at the book launch at Bulange in Mengo, Kampala.

Kampala in the State Kingdom of Buganda:

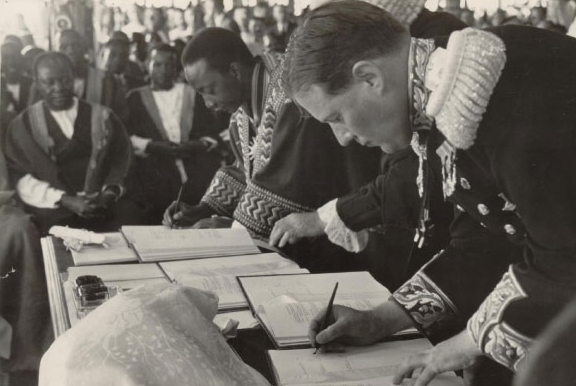

Kabaka Ronald Mutebi on Wednesday, 25th May 2016, launched a book about the struggles of his late father and former Buganda king, Edward Muteesa II, touching on Uganda’s history before and after independence.

The book titled The Brave King, revisits the stories of Muteesa’s exiling, first between 1953 and 1955, and again from 1966 to 1969 when he died in London. The author, Mr Patrick Makumbi, drew from the documents preserved by his father, 99-year-old Thomas Makumbi, who was an official at Mengo, Buganda’s power capital.

“I was very happy to write the preface to this book,” Kabaka Mutebi said, adding: “It will help the readers understand what Kabaka Muteesa went through in those days.”

When Mutesa was exiled in 1953, the older Makumbi, the father of the author, led a team of six Buganda officials to negotiate with the British about the king’s return to Buganda, which was secured in 1955. The other members of the team were Mr Apollo Kironde, Mr Matayo Mugwanya, Mr Amos Sempa, Mr Eridadi Mulira and Mr Ernest Kalibbala.

Kabaka Mutebi, while officiating at the function, called on more people to document what they saw during those days, saying “it is a good thing” that some of those who witnessed or participated in the events are still alive. Muteesa himself wrote about the period in question in his autobiography, The Desecration of my Kingdom, and Kabaka Mutebi’s endorsement of Mr Makumbi’s new book will be seen as an extension of the kingdom’s bid to manage the narrative.

Mr Apollo Makubuya, Buganda’s third deputy Katikkiro, at the launch held at Bulange-Mengo said there have been attempts to misrepresent history by “those who do not like us”.

Accusations and counter accusations of betrayal between Buganda Kingdom and Obote are rooted in a rather happy start, when Buganda’s party Kabaka Yekka (KY) teamed up with Obote’s Uganda People’s Congress to defeat the Democratic Party and form government at independence in 1962.

But the two centres of power soon quarrelled violently and were involved in what many have regarded as a critical turning point in Uganda’s history. The army, on Obote’s orders, stormed Muteesa’s palace on May 24, 1966, killing multitudes and forcing the king-president into exile.

Mr Makubuya said his grandfather was among those killed during the attack, an occasion the kingdom commemorates yearly on May 24. He said in addition to explaining how Buganda and Muteesa suffered during that period, Mr Makumbi’s book will clarify a number of other issues, including how colonialism thwarted Buganda’s development efforts.

He said Buganda stiffly resisted colonialism and the demands of colonial governor Andrew Cohen in particular, to the extent of winning a court case in London against the exiling of Muteesa. In all its efforts, Mr Makubuya said, Buganda was consistently seeking autonomy, and that the kingdom can “never” lose sight of this objective.

Mr Makumbi, the author, said his father could not attend the launch due to old age.

The publication of the book was financed by Dr Colin Sentongo, who said at the launch that KY, which ceased to exist in the 1960s, is the only political party he has ever belonged to.

The fathers of Mr Makumbi and Dr Sentongo met with Muteesa as students at Kings College Budo, from where, Mr Sentongo said, the three men forged a life-long friendship. It is probably much for this reason that Kabaka Mutebi warmed up to Mr Sentongo and Mr Makumbi at the launch.

emukiibi@ug.

nationmedia.com

Fiscal Budget y'Ensi Buganda ebiro bino:

Posted 7th July, 2014

By Dickson Kulumba

Omuwanika wa Buganda, Eve Nagawa Mukasa

Omukyala Eve asomye embalirira y’Obwakabaka bwa Buganda eya 2014/2015 nga ya buwumbi 7 (7,411,638,600/-) .

Embalirira eno eri wansi w’omulamwa 'Okwolesebwa n’Ebigendererwa' egendereddwamu okutumbula enkulaakulana okuli; okumaliriza Amasiro g’e Kasubi ne Wamala, Masengere, okulongoosa Ennyanja ya Kabaka, okussawo etterekero ly’ebyedda, okukulaakulanya ettaka ly’e Kigo ne Makindye 'State Lodge', okuzimba olubiri lw’omulangira Juma Katebe, okuzimba olubiri lwa Namasole, okuddaabiriza embuga z’Amasaza wamu n’okuzimba eddwaliro ly’abakyala.

Nagawa yagambye nti ensimbi zino zisuubirwa okuva mu Buganda Land Board, Amasomero, Minisitule ez’enjawulo, mu bupangisa, amakampuni g’Obwakabaka, ebitongole ebigaba obuyambi n’obuwumbi buna okuva mu Gavumenti eya wakati.

Ng’ayogera mu lukiiko luno, Katikkiro Charles Peter Mayiga yasabye abantu okutambulira ku kiragiro kya Kabaka eky’abantu okujjumbiro ebifo by’obulambuzi era n'ategeza nti pulojekiti zonna Obwakabaka ze butandiseeko ssi zaakukoma mu kkubo, zirina okumalirizibwa n’olwekyo enkola y’okunoonya Ettoffaali ekyagenda mu maaso kubanga Kabaka ayitibwa mufumbya Gganda n'antabalirira batyabi- ensimbi zikyetaagisa.

Olukiiko luno lwetabiddwamu abakiise bangi ddala ne baminisita ba Kabaka nga lwakubiriziddwa, Sipiika Nelson Kawalya eyagambye nti embalirira eno abakiise basaanye okugenda n’ekiwandiiko kino, bwe banakomawo mu lukiiko luno basobole okugiyisa.

Uganda Senior Police officers are facing eviction from Buganda State Police Barracks:

By Simon Ssekidde

Added 31st May 2016

Currently Mpigi Central Police station is faced with the challenge of housing

Officers at Mpigi Police Station gear up for deployment recently. (Senior officers have been told to leave the barracks).

Senior Police officers at Mpigi Central Police Station have been asked to vacate houses in the police barracks and rent rooms outside the barracks.

In the letter dated 23rd May 2016, authored by the District Police Commander, Ahmad Kimera Sseguya, he directed all officers from the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP) and above to immediately vacate the houses where they are currently staying.

According to Kimera, all officers from the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police and above are not allowed to sleep in the police barracks because they receive housing allowance in their salary every month.

“We have junior officers who are renting outside the barracks yet they are supposed to sleep inside the Police barracks, these senior officers are supposed to sleep outside the barracks and not inside because their housing allowances are consolidated in the salary” Kimera said.

Currently there are nine Senior Police officers sleeping in houses inside the barracks at Mpigi Central Police station who are facing eviction according to Kimera.

Kimera added that Cadet Officers are however excused because they are not yet confirmed ASPs and therefore they do not receive housing allowances.

Currently, the station is faced with the challenge of housing.

One of the officers who is facing eviction but preferred enormity, said the directive came at a time when they have no money to rent rooms outside the barracks and that they are expensive which they cannot afford now.

“We cannot afford to rent rooms outside the barracks now because they are expensive, we are still looking for money to take our children to school and they are now asking us to leave the barracks” he said.

'Paasita' eyeeyita Yesu bamuggalidde: Agaana abagoberezi be emmere enfumbe, okugenda mu ddwaaliro, n'okusoma:

POLIISI mu disitulikiti y’e Nakaseke ekutte ab’enzikiriza egaana abantu okulya emmere enfumbe, okugenda mu malwaliro n’okutwala abaana ku ssomero abaabadde bakubye olukuhhaana okusaasaanya enjiri yaabwe

Emu ku makanisa amanji agagoberera ISA MASIYA mu nsi Buganda.

POLIISI mu disitulikiti y’e Nakaseke ekutte ab’enzikiriza egaana abantu okulya emmere enfumbe, okugenda mu malwaliro n’okutwala abaana ku ssomero abaabadde bakubye olukuhhaana okusaasaanya enjiri yaabwe.

Baakwatiddwa ku kyalo Tongo mu ggombolola y’e Kapeeka mu disitulikiti y’e Nakaseke.

Omwogezi wa poliisi mu kitundu kya Savana, Lameka Kigozi yategeezezza nti abaakwatiddwa baggaliddwa ku poliisi e Kiwoko ne mukama waabwe Emmanuel Semakula 35, ng’ono yeeyita ISA MASIYA era agamba nti agaba n’emikisa.

Nb

Ensi Buganda ejjudde nyo eddini. Ono naye agenda kwefunira linya LYA SADAAKA (ekiweebwayo) MU DDINI ENO EYA TONDA nga Baganda banaffe wano e Namugongo bwebajjukirwa okukamala.

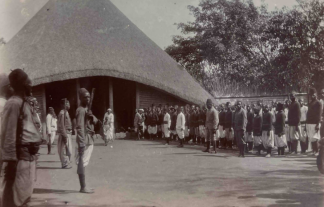

Churchill with the King of Buganda Daudi Cwa II at Kampala, 1907

Churchill with the King of Buganda Daudi Cwa II at Kampala, 1907

Make A Comment

Comments (0)